Nizam ul-Mulks political thought

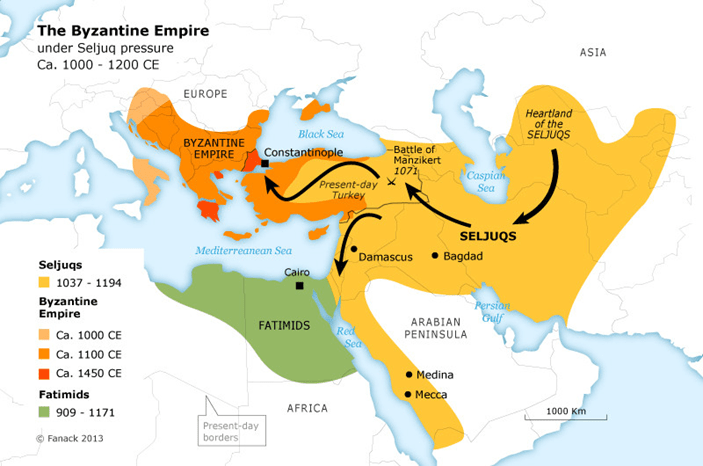

Nizam ul-Mulk has been considered the brains and foundation of the Seljuk Empire. The Seljuk empire was a Muslim-Turkic state founded by two brothers Tughril Beg and Chaghri Beg in 1037. From their heartland in modern-day Central Asia, they rapidly overran Iran, Iraq, the Levant, and the Hijaz. They famously defeated the Byzantines in 1071 at the Battle of Manzikert, leading to the expansion and conquest of Anatolia by Oghuz Turkic tribes. Nizam ul-Mulk was the grand vizier for Sultan Alp Arslan and Sultan Malik Shah, who ruled the Seljuk Empire at its peak. Originating from a Persian background, Nizam ul-Mulk was in a prime position to administrate and unite the empire and conquered territories. Nizam is well known for his authorship of the Siyasatnama (Book of Politics), which was written on the request of Malik Shah to guide governmental behaviour practiced by princes and viziers. It has occasionally been compared to Niccolo Machiavelli’s treatise titled “The Prince”. This article will expand on some of Nizam’s political thought and solutions to troubling issues within the empire. This includes his reaction to banditry and heresy as destabilisers of the realm, the oversight of intelligence institutions, the apolitical wisdom of the King’s boon-companions, the ethnic makeup of the army, and the question of whether a King should be feared or loved.

Banditry & Heresy

A massive issue plaguing the mind of Nizam and the Sultans was the existence of non-Sunni Islamic sects, specifically the Batini’s (Nizari Ismailis, often referred to as the Hashashin, the Assassins) – present in Iraq and the castle of Alamut. Batini’s relied on underground networks of Da’is (preachers) that fermented revolt in various urban and rural centres through undercover conversion. The Seljuks also faced considerable trouble with the Dailamites – a Twelver Shia ethnic group prevalent in the mountainous regions of Iranian Mazandaran and Gilan. The Dailamites made up the elites and ruling classes of the Buyid Empire conquered by the Seljuks. The Siyasatnama gives guidance and examples on how to deal with what Nizam considered treacherous subjects within the Empire. In the case of the Dailamites, he branded them as bandits and heathens. They are described as raiders who spread corruption and as “pouncing on every beautiful woman or boy that came along and taking them inside and committing immoral acts.” As a result, Nizam withdrew his forces from the conquest of Hindustan (India) and set aside a contingent of Hanafi Turks to oppose the “Dailamites, the atheists and the Batinis, and they were all exterminated.” Justification for the extermination of the Dailamites was influenced massively by their actions against women and children. Any group that attacked women and children justified a mass mobilisation against the perpetrators and validated extermination. The victims in this case were Muslim Arabs and Iranians, two groups not related to the Turkic Seljuks. To Nizam, the state inherently must defend women and children if they share the same faith, regardless of their ethnic group. This is a far cry from the actions of Middle Eastern rulers today, who act on nationalist tendencies and often engage in the same abuses against women and children, let alone redeploying armies from different fronts to get revenge and wipe out the perpetrators.

Nizam was very particular about his choice of employment in relation to other regions. He refused to hire Iraqi secretaries because of the prevalence of Batinism in Iraq. The fear of infiltration loomed large, and he was adamant in keeping statecraft homogenous in the hands of “orthodox schools” and the “Turks”, who he considered synonymous with orthodoxy (that is, Sunni). In one report, Sultan Alp Arslan rescinded an appointment offered to Dhikhuda Abaji, an Iranian, as his secretary due to accusations that he was a Batini. Abaji rejected the claim, proclaiming that he was a Twelver. Alp Arslan replied, “O cuckold, what is good about the Rafidis that you make them a screen for the Batinis?.” The Nizam and Alp Arslan remained extremely particular that any state officials must necessarily be part of the “orthodoxy”; any deviation, even if not Batini, was considered a screen of the Batini’s and a threat to the Seljuk state.

Intelligence

Sultan Alp Arslan distrusted the concept of intelligence agents. When asked why he had none, he replied, “Do you want me to cast my kingdom to the winds and alienate all my supporters?”. According to Arslan, the existence of elaborate intelligence agencies would lead to the enemies of the state engaging in bribery of intelligence officials, considering that the state would appoint their “favourites”, who would not pay great attention to the intelligence officers owing to their high status as “favourites”. As a result, the enemies of the state would curry favour with the intelligence agents and bribe them, thus compromising the state. Intelligence agents would end up reporting bad news about the “favourites”. Unfavourable reports would initially be ignored, but all it takes is for one bad report to stick leading to the “favourites” falling out of favour and undermining the state’s unity.

Nizam agrees with Arslan’s views but nonetheless affirms that it is a necessity to retain intelligence agents and considers it “one of the rules of statecraft”, the condition being that there is great oversight to ensure consistent reliability. Nizam’s choice to include Arslan’s views on intelligence agencies shows his dedication to distinction in the field of intelligence. It must be meticulously curated with constant oversight for it to be an effective form of governance and unity.

The King’s Companions

Nizam discusses the necessity of suitable “boon-companions” for the King, separate from noble’s and state workers. They must exist in a state of complete independence and should not hold office. Owing to their companionship with the King, it is more than likely that they will abuse their power and cause corruption. Instead, they should be completely neutral in the affairs of the state and act as honest advisors and dear friends to the King. The King should have the freedom to express any opinion, no matter how frivolous or serious. Any manner of ideas should be passed through them for independent advice they give out of good faith and close friendship. They must be consulted with after meetings with ministers, nobles, and statesmen and should allow the king to relax. Nizam states that excessive company with ministers, nobles and statesmen will make these groups arrogant and feel like they have the power and favour to do as they please without any real consequence. Nizam, in opposition to Machiavelli, believes that a King should be loved over feared by his people, but in manners of statecraft, officers should operate in a state of fear, while boon-companions should be familiar. Companionship with boon-companions will help the King stay normal, living like a normal man without always being burdened by his role of a King, lest he become excessively harsh and isolated. Due to their closeness with the King, they can act as formidable and loyal bodyguards should the time arise and protect him from conspiracy. They have the ability to call the King out on unreasonable beliefs and can hear ideas and thoughts that are not suitable for the ears of the ministers.

Races of Troops

Nizam believes that troops should always be mixed and not exclusively of one race. When they are all of one race, they lack zeal and are apt to be disorderly. It is for this reason that he supports the incorporation of races considered disloyal to the empire to retain regiments within the armed forces, like the Dailamites to assimilate them into the realm. A multi-ethnic army will constantly be in competition with each other to preserve their name and honour lest anyone say that a specific race is slack and ineffective. Consequently, they would not retreat until they had defeated the enemy. Over time, the different races would begin to respect each other as valiant warriors in their own fields. For example, the Dailamites would garner respect for being fearless and reliable infantrymen, while the Turks would be respected for their exceptional bravery and formidable role as cavalry and horsemen. The multi-ethnic aspect of the army must not fuse and become a melting pot but should stay segregated.

Should a king prefer to be loved or feared?

Contrary to Machiavelli’s binary view on fear and love – that the king, if he had to choose between being loved and being feared – should be feared, Nizam approaches the question more holistically. Machiavelli’s beliefs are grounded on a pragmatic, secular foothold. He chooses pragmatism over morality and advocates for a separation between personal religious beliefs and practical requirements of government. In comparison, Nizam views leadership as inherently religious. His Islamic principles compel him to advocate for a king being fair and just to his subjects. Rather than approaching it from a realist perspective, Nizam refuses to discuss whether a king should be just and fair depending on the political landscape; rather, it is an absolute requirement to be both based off his Islamic principles. He emphasizes that if a king follows Islamic principles of justice, mercy, and compassion, he will inevitably gain the loyalty of his subjects as evidenced by the example of the Prophet and his companions. He compares the king’s duty to a shepherd tending to his flock; he is required to provide protection and sustenance while being firm when it is required. He focuses on the concept of justice. An accurate practice of justice will inspire love, and its consistent enforcement will inevitably inspire a healthy degree of fear. Nizam approaches the art of the state through a passionate, fair, and just rule lens guided by religious legal systems and modes of morality.

Leave a comment