Lord Cromer and Egypt:

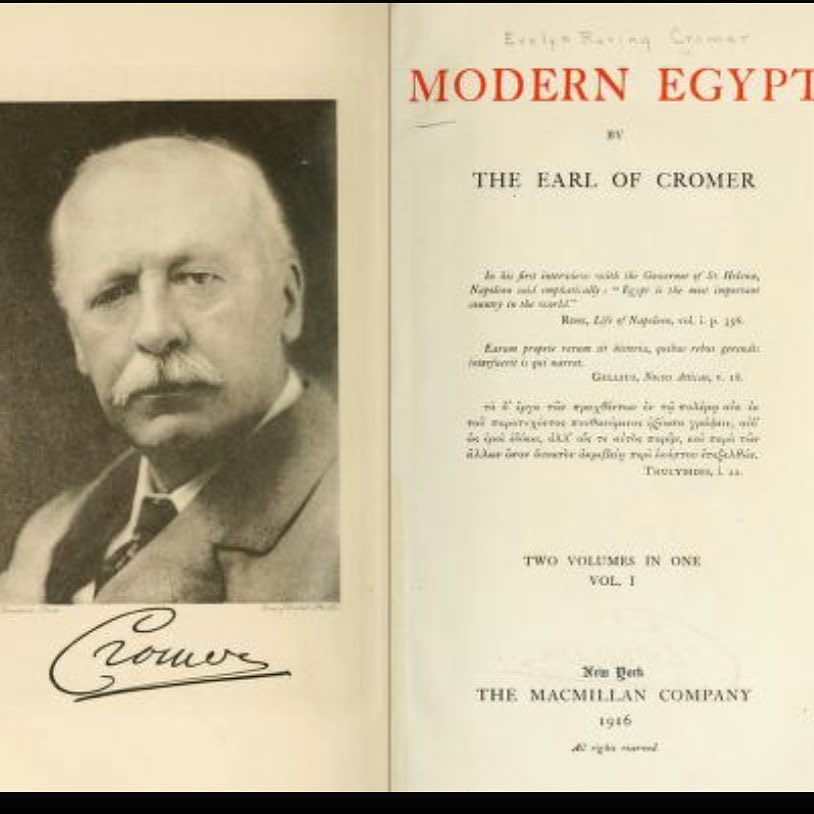

Lord Cromer (born Evelyn Baring) was a prominent British colonial administrator in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. As the British Consul-General in Egypt from 1883-1907, he was synonymous with British rule in Egypt. His background in finance was the foundation of his appointment given the debt-crisis Egypt faced. Through substantial administrative experience and cultural exchange, Cromer saw himself as an authority on Egypt, Arabs, and Muslims. With the typical arrogance of a noble British colonialist, Cromer outlines his experiences and opinions through an orientalist lens, fashioned with a superiority complex and an innate belief in the “white man’s burden”. Cromer’s memoirs, Modern Egypt was published in 1908, a year after he stepped down. It serves as a memoir and justification for his policy decisions throughout his tenure. Evidently it is a bias piece from a man foreign to Egypt, yet I believe Cromer’s experiences provide an invaluable insight into a colonial administrators view on Islam and Muslims after living side by side with them for decades. I would argue that their opinions on Islam and Muslims are more progressive and understanding than those involved in modern day politics, whether that be a conservative, a liberal or a leftist. British colonialist accounts, as I have mentioned before, are 100%, objectively not objective, everything is viewed from a paternalistic lens and a conviction that their way of life is superior, but through this, we know exactly where they stand and why they think the way they do.

On civilisation:

Cromer describes the Englishman as constantly thriving to attain a high degree of eminence in Christian civilisation; rather than proselytise, he will endeavour to use his inherent Christian principles as a guide for relations between man and man. Christianity in the Englishman’s sense is tied to England’s Puritan history and their ancestry, who have passed down a Christian national character through blood. His view on the Englishmen bares great resemblance to the works of South Africa Boer nationalists in the 19th century – romantics who proclaimed the importance of pure blood imbued with the morals of Protestant Christianity. Both cases are ironic, considering a brutal history of colonisation and exploitation.

In comparison, the Egyptian holds fast to the faith of Islam, which he calls a “noble monotheism”. Belief in Islam and monotheism takes the place of English patriotism, tied to ethnicity, Anglo identity, the empire and Anglicanism. Blood plays almost no role owing to Islamic belief that monotheism is pure and is for all races and ethnicities. Intertwining the English identity, marked by blood with Protestantism helps to justify the white man’s burden in the perspective of the colonialists. Owing to their blood, imbued with Puritan principles, the Englishman has an inherent claim to superiority, hence it is their burden to civilise the lower races and religions of the world. Through a certain, peculiar lens, this mentality does not dismiss the “more backwards” races and religions, it accepts any good qualities that they may have. Rather, it leads to a paternalistic outlook that isn’t necessarily bloodthirsty or dismissive, although in many cases they go hand in hand.

For example, Cromer praises Islam as a faith that gives grace to “barbarian races”. It imbues “poor, backwards” tribes and people with spiritual consolation and material blessings in this world, and in the hereafter. He states, “it cannot be doubted that a primitive society benefits greatly by the adoption of the faith of Islam.” He quotes Sir John Seeley, who says that whenever a barbarous tribe has risen above barbarism, it has done so usually through conversion to Islam.

The Westernised Muslim:

Cromer’s experience with Islamic modernists and orthodox Islamic sheikhs give him great insight on what he considers to be reactionary movements in Islam, as a consequence of colonialism and the spread of “modernism”.

He describes the “Europeanised Egyptian” as an Egyptian Muslim who studied in secular British schools and visited Britain/Europe. Cromer is wary of the Europeanised Egyptian’s Islam. He considers them generally agnostic and notes the gulf between him and an alim (man of knowledge of Al-Azhar (the most prominent religious seminary in Egypt). A thoughtful European Christian would look at the alim with interest as a representation of an ancient faith, which consists of many qualities worthy of respect to an intellectual European. He may also sympathise with the alim because he is religious, like the Christian European. On the other hand, the Europeanised Egyptian will look at the alim with disdain atop his pride as a modern intellectual who has a monopoly on what could uplift Egypt. The alim to him is a relic of the past and a deterrence to Egyptian success.

Cromer states that the Egyptian Muslim after passing through the European educational system, loses his Islam and his Islamism. He cuts himself off from practice and spirituality, albeit he nominally considers himself a Muslim. He avoids what is best of the creed and accepts what is lax. However, it is almost never the case where he sympathises with Christianity. He is often more intolerant against Christians compared to a normal, orthodox Muslim not of the upper classes. He holds a bitter hatred towards Christians and sees them as a rival that preoccupies the positions, he feels he deserves in the colony of Egypt. While the Europeanised Egyptian may adopt the traits of his European teachers, he often begins to despise European civilisation. He can see firsthand that it is not as glamorous as advertised, and frequently observes the defects of the Englishman or the Frenchman, which, owing to his own arrogance, cannot accept. He will accept existing faults in his civilisation but won’t accept moral grandstanding from a civilisation also riddled with imperfections, always embroiled in conflict, theft and heavy measures against colonised people. The result is that the Europeanised Egyptian returns to Egypt bitter towards the West. As a result, he often adopts Western ideology that if adopted, ironically become anti-Western. They may, out of disgust pick up the works of Karl Marx (a Western author) and decide to import Marxism as a tool for anti-imperialism and self-rule. They may also be inspired by European Nationalism and import it as a tool to create a unified native identity to fight against its occupiers. (albeit marred with pseudo-science and often exclusion of minorities)

The Europeanised Muslim will return as a paradox, European in his mannerisms, speech and culture, but more anti-European than many the less educated natives directly suffering under their colonial rule. This is due to their unfamiliarity with the concept of race and humiliation that the Europeanised Muslim becomes acutely aware of when studying in the West, and their Islamic beliefs which explicitly condemn blanket hatred of races or nationalities.

Muhammed Abduh and Sheikh Bayram:

Sheikh Muhammed Abdu was an Egyptian alim and an Islamic reformist thinker associated with Lord Cromer. Abdu believed in the adoption of various European ideas to reform and revitalise the Islamic world. Cromer speaks highly of his character as a “superior type of brethren”. He did not consider Abdu as a Europeanised Egyptian or a “bad copy”, rather, he considered him a “genuine Egyptian patriot”. As highly as he speaks of Abdu and his attempts to find a middle ground between what Cromer describes as fanatical Muslims, and completely Europeanised Muslims, he still questions his faith. Cromer suspected that Abdu was in reality an agnostic. Of course, this is Cromer’s personal opinion and cannot be taken as proof that Abdu didn’t take his religion seriously. As high as he speaks of Abdu and his attempts to modernise while remaining an Egyptian patriot, he clearly seems to not have paramount respect for him given the grand accusation against Abdu’s faith.

The one person Cromer speaks only highly of is Sheikh Mohammed Bayram, who had passed at the publication of the book. Sheikh Bayram is described fondly as a devout Muslim, far more earnest than Muhammed Abdu and other contemporaries. He is the personification of a true Egyptian and a true Muslim, free from being Europeanised, which Cromer sorely cringed at. Sheikh Bayram would practice his faith and complain over the state of the Muslims, specifically their decadence and adoption of European habits. Ironically, Cromer never rebuked Sheikh Bayrams distaste for Europeanisation, tied intrinsically to his faith. He held a great amount of respect for Sheikh Bayram, stating that the Pashas, place-hunters and corrupt sheikhs were not worthy to unloose the latchet of his shoe. Sheikh Bayram’s faith is described as founded on a rock, and any tendency to disparage Islam disappeared when people met him owing to his magnificent character derived from his faith.

Cromer respected Sheikh Bayram especially for his dedication and firm belief in his faith. He complained about the situation of Muslims, but he never wanted to become like the Europeans. In a conversation with a Christian, the shared spiritual nature of both would attract, but when it came to debates and fundamentals, the Sheikh would not budge. He thought, wrote and acted to try and resuscitate his faith, which once ruled from Spain to India, led the golden age for science and gave equality to all humans regardless of gender or race. A faith where its followers refused to be oppressed and strove to do good and contribute to the sciences. Lord Cromer claims to heartily sympathise with Sheikh Bayram.

Conclusion:

Cromer, surprisingly to the reader who expects a European absolutist supremacist islamophobe, ends up with sympathy, not being against the Islamic world rising again and contributing to civilisation. Cromer dislikes and insults the Egyptian and the Muslim that studies in the West and becomes thoroughly westernised. He see’s them as cheap copies and lacking pride. He has a positive opinion on Islamic civilisation and its positive impacts on what he considers “barbarians”. While he retains disagreements, Cromer respects Islam as a faith and as a civilisation, while critiquing it in his own Orientalist way influenced by his upbringing and his views on Anglo superiority. Unlike the French, Cromer never insults Islam. He respects the traditional Muslim, proud of his faith but open to some forms of modernisation in relation to science, rather than creed, culture and lifestyle. The stereotypes discussed of the Europeanised Muslim persist today, and Cromer’s book is as relevant as ever. In respect to the revival of Islamic unity and civilisation, he rejects that it is a dead body and is willing to admit that it will likely awaken. It has been 116 years since he published his book. Many things remain the same, and many things have changed.

27/11/2024-ghurkan-

Leave a comment