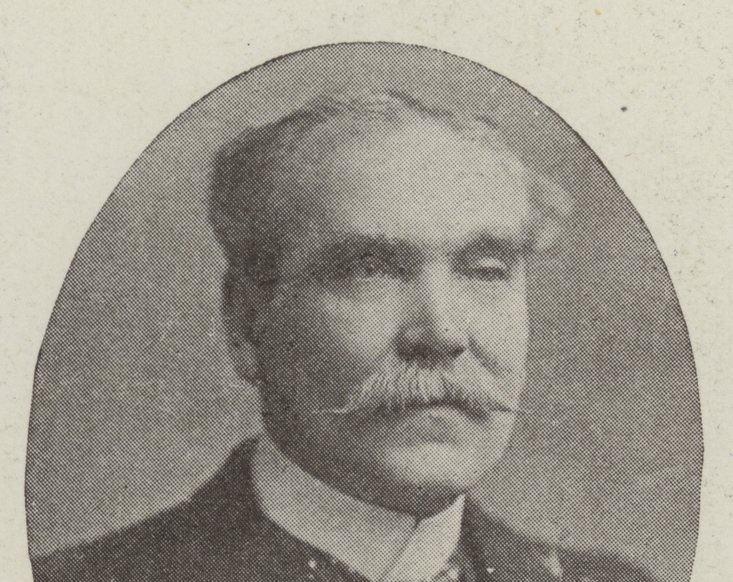

Sir William Wilson Hunter was a Scottish historian, and a prominent member of the Indian civil service based in the Bengal province. Hunter joined the Indian Civil Service (ICS) in 1862 before being posted in Bengal. From 1862-1875, he served in various capacities in Bengal, including analysis, administration and governance. During this time he gained a considerable amount of experience and knowledge on the internal affairs of India and its people. Hunter arrived in India 5 years after the 1857 Indian mutiny – a failed mass revolt with Hindus and Muslims jointly fighting against the British empire. The British placed majority of the blame on the Muslims, accusing them of playing a disproportionate role in fermenting the rebellion, owing to the ferocity in which they fought. In 1871, Hunter published his book, The Indian Musalmans: Are They Bound in Conscience to Rebel Against the Queen?, based on his observations working in Bengal. While the book pertains to Bengali Muslims, Hunter makes comments on the general Indian Musalman and their beliefs, and discusses his limited understanding of Islamic theology to analyse whether the Indian Musalman will always be rebellious against his Christian colonial overlord. He asserts that the Indian Musalman will never truly be loyal to the crown due to his faith, and points out the “wahhabi rebellion” as an example, giving little hope to other colonial administrators. His book wasn’t read without any detractors, given that the prominent Muslim modernist, Sir Syed Ahmad Khan, wrote a damning review blasting Hunter’s understanding of Muslims, “wahhabis” and Islamic theology. This article will outline Hunter’s key points on his belief that the Indian Musulman can never be loyal. It will also elaborate on his personal view on Muslims, and his perception of the “wahhabis” and how it is shockingly similar to rhetoric about Muslims in contemporary times. Sir Syed’s adverse reaction to Hunter will also be put into context specifically with his debunking of Hunter’s inaccuracies and biases.

Hunter’s view on Muslims:

Hunter see’s Muslims as volatile and disloyal subjects, always willing to pick up arms if their religious freedoms are infringed upon. Muslim’s are described as a morally decent and intellectually bright community but over-zealous in their desire for self-rule and autonomy to practice their faith without any encumbrance. He doesn’t see this desire as unreasonable, it is a natural human reaction to want to defend one’s beliefs and lifestyle, in fact, Hunter respects it. At the end of the day, Hunter is loyal to the empire, to Britain, its values, its rule and its supremacy. His respect is irrelevant in his goal to uphold and strengthen the empire’s rule in India.

The education of Indian Muslims, prior to the British, was wholly superior to any other system present in the region, albeit inferior to the British according to one British statesman. He claims that it is not to be despised as it secured an intellectual and material supremacy, and the only means in which Hindus or Christians could find success. Before the country passed to the British, the Muslims were the political and intellectual power in India, infinitely superior to the alternative in the words of Hunter. During the first 75 years of British rule, they relied on Indian Muslim systems as a means of producing officers for the civil service. Once the British had come up with their own system, they flung aside the old Muslim system and closed all avenues of public life for the Muslim youth. He admits that this was a folly move which caused great discontent amongst the Muslim’s, feeding onto their hatred for the British as an empire which treats Muslims as disposable. Indian Muslims observed first hand that the British used Muslim superior institutions to train a new generation of officers that favoured the Hindu’s in all other forms of public life, something that Hunter laments. He doesn’t entirely blame the Indian Muslims for their hatred and bitterness towards the British. In fact, he believes that a reason for Muslim resistance to the empire is due to the empire’s unfair discrimination against the most educated sector of society.

Hunter clearly respects the intellectual and political tradition of Muslims and labels them the “best people”. In his own words:

“But important as these two sections of the Muhammadans may be from a political point of view, it has always seemed to me an inexpressibly painful incident of our position in India that the best men are not on our side. Hitherto they have been steadily against us, and it is no small thing that this chronic hostility has lately been removed from the category of an imperative obligation. Even now the utmost we can expect of them is non-resistance. But an honest Government may more safely trust to a cold acquiescence, firmly grounded upon a sense of religious duty, than to a louder-mouthed loyalty, springing only from the unstable promptings of self-interest.”

Hunter and Syed on the “Wahhabis”:

The term “wahhabi” for those Indian Muslims who picked up guns and sabers against the Sikh empire is a misnomer. The movement led by Syed Ahmad Barelvi in the early 19th century to overthrow the Sikh regime that oppressed its Muslim subjects has no tangible relation to the Wahhabist movement originating in the region of Najd (modern day Saudi Arabia) – it had no theological or jurisprudencial similarities with the wahhabis of Najd, who followed a distinct form of Islamic jurisprudence and theology. Both were quite Puritan in their outlook, and the Arab Wahhabis were viewed as radicals and extremists by the British. They applied this label to Ahmad Barelvi as a means of delegitimization. The use of the term wahhabi, interchangeable with salafi, as a derogatory term to label any armed Islamic movement is still prevalent today. If a Muslim in the West does something not aligned with the status quo, they are labelled a wahhabi. If an Islamic movement picks up arms against a government or an occupation, they are labelled wahhabi. Prominent movements in Afghanistan, Palestine, Chechnya, Kosovo, Kashmir and Rohingya have all been labelled wahhabi, regardless of the fact that they have very little in common with wahhabis. The Jihad movement led by Ahmad Barelvi was in fact not based on theological and jurisprudencial revival, but on political will to depose an oppressive ruler, a purification from what Ahmad Barelvi considered social evils at odds with Islam. For example, he viewed the taboo on divorcees getting remarried, and forced marriages as completely un islamic and endeavoured to fix both. His movement was heavily Sufi inspired, a trait despised by actual wahhabis. His teacher was a Sufi of the Naqshbandi order, as was the Syed. It would be more accurate to label the Syed’s crusade as the “jihad movement” as it was described by his descendent, Syed Abul Hasan Ali Nadwi.

Hunter discusses the Jihadist movement and its followers with awe. While he only had interactions with the Jihadists in the Bengal region, he finds it impossible to speak of them without respect. According to Hunter, many of the Jihadists retain their zeal for their religion from a young age to their deaths, without poisonous influence from corrupt religious authorities or western evils. He compares them to the civilised man, cribbed in cities and only permitted to travel around the world with a mass of luggage. The Jihadist thinks purer and fresher thoughts than the work a day in the world.To Hunter, the isolated wanderings and lonely foot journeys are more reminiscent to the life of the Englishman’s ancestors, living open in Merry England in the company of wild animals and rolling mores. The Jihadist missionaries are described as the most spiritual and least selfish type of the sect, and as similar to the Christian pilgrim who passes from the town of destruction to the Celestial city.

Regardless, Hunter pins the blame on Muslim sedition on the so-called “wahhabis”. He might respect them, but he is beholden to his own God’s, whether that be Jesus or the pseudo-divine British empire. The blame on sedition against the British empire is laid on the Jihadists, an accusation that is staunchly contested by Sir Syed. Sir Syed points out that Hunter’s version of history is only relevant in the Bengal. The Jihadist homeland in Punjab was focused on fighting the Sikh state. They had no interaction with the British empire, and were a political response to Sikh oppression. Sir Syed, anglophile that he is, claims that the British empire leaves Muslims alone, therefore the Jihadists would not consider attacking the British empire. According to Hunter’s own regretful words, this is not the case given the British completely closing the door on all forms of public life for Muslims. Some sectors of the Europeanised Muslim end up being more sympathetic to the Empire than its servants. There is still truth to what Sir Syed says. Any Muslim sedition against the British empire is automatically labelled as wahhabi by Hunter. He describes the Pashtuns of the North West Frontier Province (NWFP) as wahhabi and jihadist. This could not be further from the truth. The Pashtun tribes of NWFP turned their backs on Ahmad Barelvi due to their disdain for his reformist tendencies. The Pashtuns are described as hanafi extremists rebelling for their own reasons, distinct from the overt Jihad from the Jihadists.

Conclusion:

Hunter, like Cromer, has great respect for the proud orthodox Muslim. Hunter has seen first hand the intellectual and martial prowess of Indian Muslim’s and appreciates their dedication to their faith. He uses Christian terminology and comparisons to justify his respect. He laments the British treatment of Muslims and dislikes how the most competent Indians aren’t “loyal” to the empire. Hunter still prefers these “disloyal” Muslims over the loud-mouthed non-Muslim Indians who obey every command out of convenience to curry favour with their overlords. He betrays his bias. His words are regardless riddled with inaccuracies. Every Muslim who picks up arms is deemed a wahhabi extremist which is more often than not the furthest thing from the truth. The use of the word is a means of dismissing justified reactions against colonial occupation and lite-apartheid. Hunter ultimately “respects his enemy” and makes excuses for them, it is my opinion that he is simply misinformed on the matter, considering that his base was always the Bengal. His appreciation of the wandering missionary and fighter is reminiscent of the opinions of General Nick Carter from his time in Afghanistan. To Hunter, armed resistance is begrudgingly justified and respected, although never appreciated. It is more respectable than being a deceptive flatterer with no manly convictions based on something greater.

27/11/2024 -ghurkan- (draft)

Leave a comment